by Tanzil Chowdhury

To many, the ‘ACAB’ slogan may seem like little more than radical posturing. The prospect of a police-less future is so impossible that it exudes pharaoh-nic levels of naivety. So naturalized has the existence of the police become, that many think reform, rather than abolition, is the only way to advance beyond racist policing. It is akin to when Fredrich Jameson, the famous cultural theorist, once said ‘it has become easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism’.

Part of the difficulty many have in accepting calls to abolish the police, seem to lie in the absence of practical, short-term solutions towards abolition. However, there has been serious engagement on police and, relatedly prison, abolition in both activist, academic circles and even popular press. This post, largely aimed at communities and campaigning groups, argues for a more modest but related position against engagement with the police. By no means exhaustive, these are not purely positions of principle but rather concrete arguments that demonstrate how engagement can and has undermined the ability to hold the police to account.

Before detailing these positions, largely restating things written and heard elsewhere, it is worth recognising the strategic position that other groups and individuals may have in specifically-targeted engagement with the police. However, this article briefly argues for a general default position for non-engagement with the police and locates itself within the larger anti-racist tradition of prison and police abolition.

Vulnerability to police intrusion and intelligence gathering

Underlying much of the argument against police engagement is the false presumption that it is a safe and effective way in addressing and resolving concerns around police racism, brutality, harassment and impunity. The argument here is that engagement invites infiltration. The police, as an institution, are largely not interested in dialogue but information gathering. Perhaps most importantly, once a person, community or organization is exposed to dialogue with the police, it leaves them vulnerable to data gathering. The nature of data gathering is such that it becomes part of a permanent archive that can be exploited and used for other security imperatives when necessary and convenient. This is painfully apparent in how disparate and entirely innocent pieces of information are pulled together to create profiles of risk about individuals in determining their potentiality to commit crime.

The police have a history of using ‘dialogue policing’ to gather intelligence. Police Liaison Officers (PLO), created in light of the appalling policing of the G20 protests and police killing of Ian Tomlinson in 2009, emerged following a report by the Joint Committee on Human Rights. The parliamentary group argued for greater dialogue with the police and criticized police units, such as the protest-intelligence gathering team FIT, for being more interested in surveillance than engagement with those exercising their right to assemble. The formal role of PLOs therefore, is to engage in a more dialogic approach with protestors.

The Network for Police Monitoring produced a report providing compelling evidence that many former FIT officers had gone on to become PLOs. The report contains several admissions by senior officers that PLOs were less concerned about dialogue and more about intelligence gathering. Among a litany of failures, Chief Inspector Sonia Davis, head of the Police Liaison Teams (PLT), gave evidence as a prosecution witness in the trial of an environmental cyclist group who were arrested on the evening of the Olympics opening ceremony in 2012. She admitted that PLTs gathered information on protesters and had been deployed at previous mass bikes rides to try to identify ‘leaders’. PLOs illustrate why dialogue and engagement with the police, more generally, is problematic and can potentially incriminate communities and individuals while posing serious challenges to the integrity and functioning of campaigns and organisations.

It’s also worth saying something about the 2015 Undercover Policing Inquiry because it also shows how engagement and working with the police can leave individuals and groups vulnerable to infiltration. There have been many shortcomings with the inquiry which, though extremely important, are not the focus of this post. Generally however, there are fundamental problems with undercover policing. One famous example, which only came to light many years later, was the infiltration of the Stephen Lawrence Justice Campaign in which police spies tried to gather information about the Lawrence family. While the family were grieving about their son who had been murdered in a racist attack, they were also trying to persuade the police to properly investigate their son’s racist murder. Police spies tried to gather information about the parents of Stephen Lawrence, including the breakdown of their marriage. They used this information to try to deflect criticism that they messed up the investigation- an investigation which, coupled with mass mobilistion from the community anti-racist campaigns, prompted an inquiry that showed the police to be institutionally racist.

Political groups have also been infiltrated. Many women have provided testimony to the undercover police inquiry that they had been tricked into having sexual relationships with people they believed to be activists but later turned out to be police officers. Police officer Mark Kennedy had lied about being an environmental activist and infiltrated many left wing groups, providing intelligence which led to the arrest of several activists at demonstrations and direct actions. During his time undercover, he had formed close friendships and sexual relationships with activists. In a legal case which eventually collapsed, involving a group of environmental activists trying to shut down a coal station in Ratcliffe-on-Soar, one of the protestors, Danny Chivers, described Kennedy not just as an observer but as an agent provocateur.

Ultimately too, dialogue provides an invaluable ‘PR win’ for the police as they are being seen to engage with communities which illustrates the police’s desire for resolution and assuages their often violent and long-lasting interventions into those very communities. It provides the illusion that they are doing something, whilst in fact they are often entirely unwilling to make any meaningful change.

Non-effectiveness of Dialogue

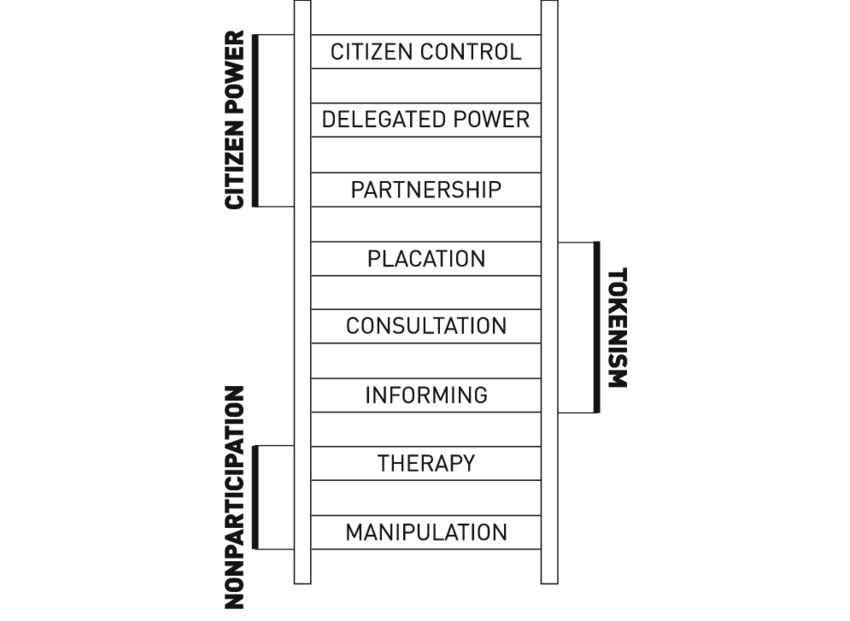

It must be said from the outset that when you enter into dialogue with a state institution like the police, the difference in expertise, in resources, in well-curated legitimacy, will always create an imbalance of power than can inform discussions and dialogue. Thus engagement is typically rendered meaningless. Consider the role of independent advisory groups (IAGs) whose role, among other things, is to ‘improve communications with groups not usually in dialogue with the police.’ In the conversations that we have had with members of the Independent Advisory Group in Greater Manchester, they have seen it as a powerless forum. To help illustrate the ineffectiveness of engagement, we can refer to Sherry Arnstein’s level of citizen participation which looks at the different levels of involvement that public and community forums can have in decisions that impact them.

This can range from manipulation at the bottom, where the forum is used as a means to dictate the responses and framing of communities concerns, through to consultation, or, right at the top, delegated powerand citizen controlwhere communities actually dictate, implement the agenda and action policy. The sense that many people get is that IAGs are more about therapy and informing at the very least, thoughare often about manipulation, with the police often steering the conversation. While members from the community get understandably angry and upset and are able to vent at the police, which is important, little gets done. Again, however, it provides the police with an absolutely vital opportunity to demonstrate that they are sincerely committed to listening, engagement and reform.

Compromises Community trust

Central to any community-led organization or campaign, is securing trust of individuals and impacted communities. It is important, not only that independence from the police is done but also that is it seen to be done. Anxieties are often stirred by working with the police, particularly in communities that have been criminalized and over-policed. Many people within impacted communities reasonably see the police as an antagonistic force and perceive any organization working with them as merely being interlocutors of the police rather than impartial brokers. It is not merely that communities hate the police (often with good reason), but that dialogue can often trigger traumatic episodes. An organization that works with the police therefore may be perceived as trying to appease the damaging work the police do and often soften the trauma they have imposed, rather than genuinely being committed to supporting individuals and families. Much anecdotal evidence gathered through protracted conversations with impacted families have spoken to this effect, often creating a deep sense of mistrust in police investigations into their own wrongdoings and a general hesitancy of the state in conducting public inquiries and inquests.

Limits Radical imaginations

Finally, engagement with the police limits our imagination. The arguments for abolition of the police are not pie-in-the-sky fantastical thinking, but well researched, forensically thought out positions. It forces us to reflecting on the role and need for the police and thinking about alternative forms of public safety. To do otherwise can blind us to the contingency of the police force. In other words we think of them as a ‘natural’ institution rather than a relatively new institution in the UK that emerged around the time of 19thcentury capitalism and that imported and exported expertise from the colonies in how it has policed communities of colour.

However, arguments of police abolition are not isolated and they necessarily require engagement with wider social structures that control racialized, gendered and classed populations. Abolition of slavery for example, required more than just disappearing enslaved people from plantations. It required society to eliminate its reliance on forced and brutal racialized labour. A similar logic is needed here. In his recent book, the End of Policing, Alex Vitale makes a broader argument against social and economic injustice, and against criminalisation and racism. He locates these injustices in the neoliberal exploitation and its spiraling inequalities of wealth and power- of which the police have a role in socially reproducing. The solution isn’t just about abolishing the police but restructuring society in such way that doesn’t require them as an institution.

The kinds of ‘short-term’ measures or ‘non-reformist reforms’ we can make, away from police engagement and toward abolition require both a discursive battle as well as a material one. The former, which has already been touched on, is questioning the presumption that the police are invested in preventing crime (what is crime? does it prevent crime in particular communities and spaces?) and that societies need ‘law and order’. The latter alternatives to policing may include initiatives such as community monitoring, divestiture (particularly toward social infrastructure like youth clubs, social and mental health care, education, sports etc), decriminalization and restorative justice. Many abolitionists have argued that we need to see policing as a public health issue not a criminal justice one. Thus, perhaps an often ignored focus on some anti-police brutality organisations is articulating and working toward these alternatives. The position of non-engagement therefore is not esoteric, ivory-tower thinking, but one which is necessary to maintain the integrity of our campaigns which works toward a more just and realizable future.