LAURA CONNELLY (NPMP)

This article is from NPMP’s annual magazine. You can see the full magazine online, and order physical copies here.

From the state-facilitated kidnap, rape and murder of Sarah Everard and the Metropolitan Police’s brutality towards women attending the vigil in her honour, to the degrading and sexist treatment of Bibaa Henry and Nicole Smallman’s bodies, recent events have shone a light on police violence against women.

These events – alongside a resistance movement sparked by a rallying cry from Sisters Uncut – have attracted the attention of a wider public to the long-standing problems of state sanctioned harm and institutional misogyny in the police (see Begum, article one). These problems are both deep-rooted and endemic. They’re often felt most by those from racially minoritised communities, those with precarious immigration status, and/or those belonging to other marginalised populations, such as sex workers.

In response to rising public concern over physical and sexual violence against women, Greater Manchester Police (GMP) has instructed officers to “do more to reassure the public, particularly women and girls, that [they] are here to protect”. But we would be foolish to listen to their reassurances, for GMP has a long history of misogyny, racism and violence.

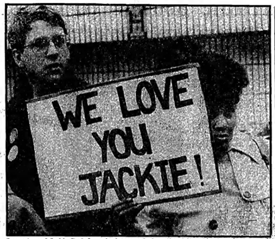

Photographer. Denis Thorpe, The Guardian, 25 February 1985

GMP did not protect Jackie Berkeley, a 20-year-old Black woman who accused two male officers of rape whilst two women officers restrained her, at Moss Side police station in 1984. Instead, they detained her for longer than legally required, preventing collection of physical evidence of the rape. Despite being able to identify three of the four perpetrators in a line-up and the fourth from a description of his clothing, Jackie was held up in court on charges of wasting police time and making a false complaint. In court, the prosecution set about assassinating Jackie’s character and, using the four officers’ (contradictory) testimonies, constructing a web of lies that resulted not only in the conviction of Jackie but – as Gus John, member of the Jackie Berkeley Defence Committee, describes – the psychological destruction of Jackie.

GMP-perpetrated sexual violence is not, however, confined to the past. According to data obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, there have been allegations of sexual misconduct against 158 serving GMP officers in the past five years. The number of allegations against GMP is higher than that for any other police force in England and Wales. In November 2019, a GMP officer was found guilty at a misconduct hearing of sexual assault, one count of assault by penetration, twelve counts of voyeurism and two counts of taking indecent images of children. At a hearing in June 2021, it was found that an officer “gained authorised access to police data regarding known sex workers, one of whom the officer then met”. We know from organisations such as the English Collective of Prostitutes that police too often abuse their power to demand free sex, steal sex workers’ money or perpetrate violence with impunity. Unsurprisingly, the state has taken up the well-worn ‘few bad apples’ narrative to explain away officers’ violence against women, but the systemic nature of the problem also manifests in GMP’s treatment of women when they experience victimisation. A recent Inspectorate report found that GMP fails to record more than one in four reported violent crimes, with particularly notable recording gaps concerning domestic abuse, harassment, stalking and coercive control – harms known to be gendered in nature. Victim-blaming attitudes among officers are rife, and contribute to women’s reluctance to report victimisation: a recent poll by YouGov found that 96% of women aged 18-24 who had experienced sexual harassment chose not to report it to the police.

In response to an awakening to institutional misogyny in the police, some, including women ex-officers, have pointed the finger at gender imbalances in the police, with two-thirds of officers across all ranks being male. But we must be clear: just as more Black officers won’t end institutional racism, more women officers won’t end institutional misogyny and the police perpetration of violence against women. To think that it will is to grossly underestimate how deeply embedded misogyny is in the culture, policies and operations of (the institution of) the police, and wrongly assume that gendered solidarity exists between women police officers and the women that they police. More women officers won’t end state-sanctioned violence against women but it will create the dangerous illusion of change and, in turn, legitimise the police.

The police have proven time and again, not only that they are ill-equipped to protect women, but also that they are quick to abuse their status to engage in violence against women and girls. With this in mind, we must resist calls for new laws and ‘better’ policing to address the epidemic of sexual violence and harassment. That Sarah Everard’s rapist and murderer probably used his knowledge of Covid police powers (alongside his warrant card and police-issued handcuffs) demonstrates the inherent problem of giving the police more powers, particularly for women and those from marginalised groups – a point that is particularly pertinent as police are set to receive more powers through the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (see Sisters Uncut Mcr, article 12).

Just as the Jackie Berkeley Defence Committee organised around GMP’s sexual violence and brutality in the 1980s, we will continue to play our part today in a growing and powerful anti-racist and feminist infrastructure to fight back in Greater Manchester and beyond. The police cannot keep us safe, but by coupling the development of a strong resistance movement with community-based programmes for public safety, we – collectively – can.